The protagonists of Babygirl and Black Doves are stuck in their “perfect” lives—and find illicit fulfillment outside them.

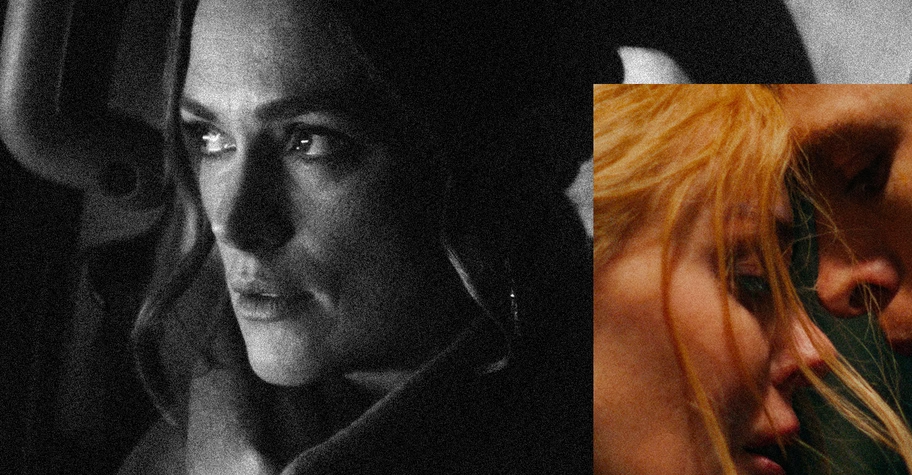

Illustration by The Atlantic. Sources: Ludovic Robert / Netflix; A24.

December 24, 2024, 7:30 AM ET

Maybe it’s the time of year, but I’ve been thinking lately about Nora, the whirling, frantic heroine of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, overspending on Christmas presents, quietly operating her household in ways that go unseen, twisting herself into knots of gaiety and performance that can only unravel. Relationships can endure an awful lot, the play asserts, but not false intimacy—not the pretense of something that should be sacred. A Doll’s House also underscores how easy it is to get trapped playing a part, particularly one that’s lavishly rewarded.

Romy (played by Nicole Kidman), the unexploded bombshell around whom the new film Babygirl is built, is one of Nora’s heirs. So is Helen (Keira Knightley), the grinning politician’s wife and dutiful mother of twins in the Netflix series Black Doves, who happens to be a spy operating under deep, deep cover. Both Babygirl and Black Doves are set at Christmastime, which allows me to argue that the former is the most honest kind of Christmas movie—not a cheerful fable about a rotund home invader, but a ferocious portrait of a woman balancing right on the edge. And like Black Doves and A Doll’s House, the movie homes in on someone who is simultaneously dying to blow up her “perfect” life and clawing to protect it at all costs.

Since Halina Reijn’s movie premiered at the Venice Film Festival this summer, with Kidman claiming the Volpi Cup award for Best Actress, Babygirl has been provoking debate about its exploration of desire, deception, and power. Romy is the immaculately assembled and impossibly tense CEO of an automation company, whose pioneering work with robotics and artificial intelligence feels almost too on the nose. Romy is optimized, down to the subtle Botox shots that limit her expression and the high-femme power suits in dusky pink that register her as a compassionate girlboss. But is she human? As she attends her office holiday party, then her husband’s theatrical premiere (Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler), then her family’s Christmas dinner at their picture-perfect house outside New York City, Romy switches fluidly between different identities. None feels authentic, at least until a messy affair with the unsettling, slightly feral Samuel (Harris Dickinson) encourages her to try out a kind of role-play that’s wholly new.

Read: The redemption of the bad mother

Much has been made of Babygirl’s sex scenes, in which Samuel, who’s both disconcertingly fearless and bizarrely intuitive, senses that Romy wants someone to dominate her—not for humiliation and abjection, but as an expression of care. In the movie’s early moments, Romy straddles her husband, simulating orgasm, before rushing to her laptop to indulge in what really turns her on; she packs lunches for her two daughters wearing a rose-patterned apron, slipping in handwritten notes that will surely mortify them; she sits in her corner office, welcoming a new class of interns, Samuel among them. Each of these roles involves catering to others, but what Samuel understands is how much she longs to cede control, to abandon decision making, to be sternly told what to do. Reijn, who also wrote Babygirl, lightly suggests that Romy’s free-range childhood in a cult helps explain her eroticization of authority, but Romy’s craving for risk feels like more than that: It’s the only way she can critique her idealized existence. “There has to be danger,” she explains late in the movie, trying to understand what she really wants. “Things have to be at stake.” The push-pull between safety and survival is the movie’s most fascinating element. As Nora says to an old friend in A Doll’s House, faced with the possible airing of her secrets, “A wonderful thing is about to happen! … But also terrible, Kristine, and it just can’t happen, not for all the world.”

Through this lens, Kidman’s performance as Romy lingers long after the final act; it’s a disturbing mix of reticence and abandon, taut composure and elemental surrender. The movie is part and parcel of Kidman’s series of works in which she embodies artifice before imploding it as we watch. As an actor, she, too, seems drawn to risk, and to the freedom and fulfilment that can come with acquiescing to another person’s creative vision. Before she was a director, Reijn was a classically trained actor, playing an “unkempt and suicidal” Hedda Gabler (as one profile put it), among other roles, before developing debilitating stage fright in her late 30s. What both she and Kidman seem to want to say with Romy is that no loneliness is more profound than realizing that you don’t know yourself at all—and that the comforts and milestones you once yearned for have become anchors that threaten to pull you under.

Helen (not her real name), Knightley’s undercover operative on Black Doves, operates within much the same space as Romy and Nora: Her family is one enormous lie that she will fight to the death to maintain. The Netflix series, written by Joe Barton (the creator of the underrated crime thriller Giri/Haji), is a darkly funny, thrillingly brutal, ludicrously self-aware yarn about underground crime networks, diplomatic crises, and espionage. Like Babygirl, though, it’s also about human connection, and the untrammelled joy of being with the people who make you feel most yourself. Helen is a member of a private spy syndicate called the Black Doves, operated by an elegant woman known only as Mrs. Reed (Sarah Lancashire). Unlike spies who serve their country, the Black Doves work for cash, selling secrets to the highest bidder. When Helen was recruited, it was because Reed sensed she was a thrill seeker with a flair for violence and a cool head in a crisis. For 10 years, “Helen” has been married to a Conservative member of Parliament who’s now the secretary of defense, bearing his children and stealing his files. In the first episode, we learn that (a) she’s been having an affair, seeking some release from the constraints of her fake day-to-day existence, and (b) her lover has been murdered, setting off a trail of bloody retribution and the near-constant threat of exposure. (The effort of maintaining her triple life, at one point, almost gets her killed when her daughter FaceTimes her while Helen is hiding from assassins.)

Barton appears to enjoy juxtaposing the banality of Helen’s life as a wife and mother—flawlessly hosting her husband’s holiday work party, sticking jewels on a crown for a Nativity costume—with the extravagant action of her secret life. Helen has been styled (intentionally, it seems) to look just like Kate, Princess of Wales: hair in long, loose waves; dressed in an endless array of expensive sweaters; and smiling, smiling, smiling. In one scene, Reed describes Helen as “a coiled spring,” and the latter’s performance of holiday jollity is so committed that you can only faintly sense her cracking at the edges. When Helen finds herself in danger, Reed summons her former work partner, Sam (Ben Whishaw), and his pairing with Helen is, for me at least, what makes the show so fun. “Hello, darling,” Sam tells her, immediately after blowing the head off one of her assailants with a shotgun. Helen, covered in more blood than Carrie at prom, crumples in joy and gratitude. “I can’t believe you’re here,” she sighs.

Black Doves is best appreciated if you don’t think too hard about the logical holes in the plot and simply enjoy the spectacle. But there’s also much more to Helen than one might expect from the genre: more sympathy for how suffocated she is by her sham marriage, her own perfect display of domesticity, her unexpectedly tender impulses as a mother, which ruin her ability to just do her job. The show’s most ruthless bosses are all women—Lancashire’s Reed, Kathryn Hunter as the wormily sinister director of a league of assassins, Tracey Ullman in a cameo I won’t spoil—which suggests that they’re all adept with secrets. For Helen, though, her fake life has become so dominant that it’s superseded her identity as a person in her own right. “I wake up sometimes and I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, Sam, because I have no idea who I am,” she says in one scene. “And neither does anyone else.”

Read: The awful ferocity of midlife desire

In the end, Black Doves suggests that Helen, like Romy, might be better off at home, but that her fearlessness and risk-taking have shown her something about what she actually wants. Late in the series, confronted in a shop by an interloper who has tried to infiltrate her family, Helen throttles her with a pearl necklace—that loaded symbol of class and status—then lets her go, shrieking, “I’m still Helen Webb, and Helen Webb doesn’t stab girls to death in jewelry stores on Christmas Eve.” I laughed at the line, and at Knightley’s regal meltdown. But it also seems to signal that all of Helen’s adventures have led her to a better understanding of herself, and to acceptance. That shift is enabled by Sam, who really does see her, and—better—sees someone worth knowing. It’s the kind of validation that can make everything else about her life and her Christmas—the strategizing, the emotional regulation, the smiling—just that much easier to bear.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.