“Obviously, the story isn’t over. I am still struggling to resume my place — with one important difference,” she wrote in “Now You Know,” her 1990 memoir, in a passage that would resonate with many who are coping with substance abuse or depression. “Now I know, before I can do anything for anyone else, I have to take care of myself.”

Mrs. Dukakis, an activist and author who formerly served as a presidential appointee on national Holocaust panels, died Friday night. She was 88 and had lived most of her life in Brookline.

In a statement, her three children said that she “lived a full life fighting to make the world a better place and sharing her vulnerabilities to help others face theirs. She was loving, feisty, and fun, and had a keen sensitivity to people from all walks of life.” They thanked “all who have touched our lives over the years or who were touched by our mother.”

Her public profile extended far beyond Massachusetts. President Carter appointed Mrs. Dukakis in 1978 to the first President’s Commission on the Holocaust, a panel that called for the creation of a national memorial and museum. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush appointed her to the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, which replaced the commission.

“Perhaps in the entire history of civilization, the Holocaust was the most important object lesson in man’s inhumanity to man,” Mrs. Dukakis told the National Governors Association in 1983 while asking the organization to help raise funds for a national museum.

“My interest is in seeing the Holocaust teach universal lessons,” she said, “to recognize the suffering of other people as we look at the Holocaust so that we will speak out against inhumanity.”

In Massachusetts, she used her role as her husband’s valued, trusted adviser to promote gender advances in the executive branch’s highest ranks from the beginning of his first term as governor.

“She insisted that Mike appoint four women to his Cabinet, and that was unprecedented,” Evelyn Murphy, who was one of those appointees, said in an interview for this obituary.

When Dukakis was first elected governor in 1974, no woman had held a statewide office. Murphy, a Democrat, became the first when she was elected lieutenant governor in 1986 and served during his third gubernatorial term.

Women also had held few Cabinet posts until Mrs. Dukakis elicited a promise from her husband to appoint four in his first term, providing them with springboards to future prominent roles.

“She has not received enough attention and acknowledgment for what she did to change the face of women’s leadership in Massachusetts,” said Murphy, who was secretary of environmental affairs in Dukakis’s first term and secretary of economic affairs in his second. “Kitty Dukakis is the one who really pushed Michael Dukakis to open these doors, and it was stunning.”

Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey posted on X that “Kitty Dukakis was a force for good in public life and behind the scenes. The causes she championed — recovery, gender equality, human rights, and more — made a real difference in people’s lives.”

Mrs. Dukakis also had a key role in her husband running for governor in 1974. He was the lieutenant governor candidate on the Democratic Party’s losing ticket in 1970, and some of his advisers thought he should run for attorney general in 1974 as a safer stepping stone.

Adamant about his qualifications, readiness, and electability, Mrs. Dukakis insisted he seek the state’s top job.

“I really wanted him to be governor,” she told the Globe in 1975 when he had been in office for several months. “Not for myself — that was where he could do more. It was what his background prepared him for.”

Long before rising to prominence in political circles — among other distinctions, Mrs. Dukakis was the first practicing Jew to be aligned with a major party presidential ticket — she was known for being part of a culturally celebrated family with deep local roots.

Born Katharine Dickson in Cambridge on Dec. 26, 1936, she grew up in what she later described as “privileged circumstances,” although not inordinately affluent ones.

Harry Ellis Dickson, her father, played first violin with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and served as assistant Boston Pops conductor under Arthur Fiedler. Her mother, Jane Goldberg Dickson, who held degrees in nursing and in social work, chose to stay at home raising her two daughters and running the household.

A strict and demanding mother, Jane Dickson thought “children should be seen and not heard,” Mrs. Dukakis wrote in describing their often problematic relationship. Her mother died in 1977, her father in 2003.

Katharine Dickson graduated from Brookline High School and, while attending college in 1957, married John Chaffetz, then in the Air Force. Their son, John, was born in 1958, but the marriage soon ended. The couple separated in 1960 and divorced a year later.

After having lived away from Massachusetts while married to Chaffetz, she moved back to Boston and began dating Michael Dukakis, who was then practicing law and planning a run for state representative.

“I knew I had found a man I could love and respect,” she later reflected.

In 1963, a week after graduating from Lesley College, she and the future governor wed. For most of their marriage, the couple resided in a red brick duplex on Perry Street in Brookline, where they raised their three children.

For the duration of their marriage, and with her husband’s steadfast support, Mrs. Dukakis fought an at-times debilitating dependency on pills and alcohol. She also suffered four miscarriages during her two marriages, adding to the burdens of her addiction.

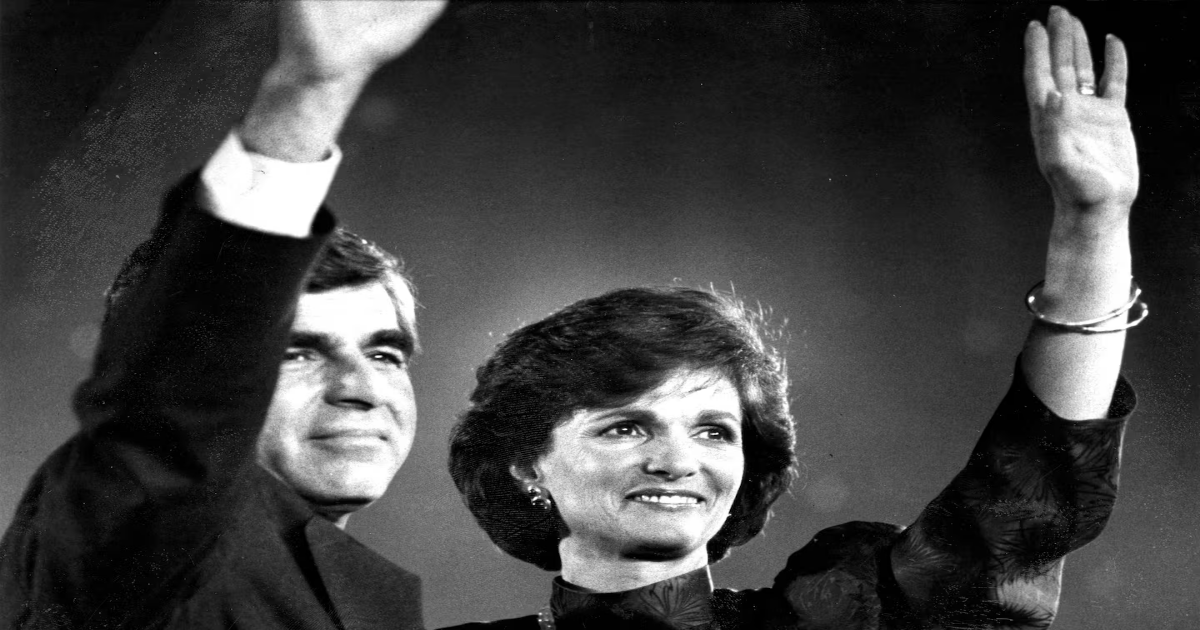

Still, her personal travails remained largely hidden from public view as her husband was first elected Massachusetts governor in 1974 and then, after losing his party’s nomination in 1978, reelected to two more four-year terms, beginning in 1982. He captured his party’s 1988 presidential nomination over a field that included Gary Hart, Joe Biden, Al Gore, and Jesse Jackson.

Running on a ticket with US Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, Michael Dukakis faced Vice President George H.W. Bush in the general election, losing decisively. The campaign was arduous and sometimes bare-knuckled, at one point dragging Mrs. Dukakis herself into what became a turning point in her husband’s fortunes, or so many observers felt. Asked during a debate if he would favor the death penalty for a criminal who had raped and murdered his wife, the candidate dispassionately replied no, he would not. He had always opposed capital punishment, Dukakis explained.

His measured, if principled, response caused an uproar, even among some Dukakis supporters. Later, according to Mrs. Dukakis, she chewed out her husband for being unprepared to answer such a blunt question. “Kitty, I just blew it,” she recalled him saying.

The rugged ’88 campaign took its toll in other ways. Not long after, Mrs. Dukakis struggled with alcoholism and depression. At one of her lowest points, in the fall of 1989, she ingested rubbing alcohol and was taken, unconscious, to a hospital emergency room. In February of 1989 she entered Edgehill Treatment Center in Newport, R.I.

There would be more relapses, as well as other substances besides alcohol that she impulsively ingested. The following April, she checked herself into Self Discovery Inc., an Alabama rehab clinic.

In 1990, Mrs. Dukakis published her unsparing memoir, written with Jane Scovell, which famously opened with this line: “I’m Kitty Dukakis and I’m a drug addict and an alcoholic.”

During the presidential campaign, she wrote in the book, “I became an episodic binge drinker” dealing with “a gaping emptiness I could not endure.”

In a column discussing the book’s revelations, the Globe’s Ellen Goodman, an admirer of Mrs. Dukakis, admitted to being troubled by its relentless focus on substance abuse and depression. Her sadness as a reader, Goodman wrote, “was the sadness of discovering that I liked someone much more than she liked herself.”

In addition to her husband, Mrs. Dukakis leaves their son, John, whom Mr. Dukakis adopted, and who lives in Boston; her two daughters with Mr. Dukakis, Andrea of Denver and Kara of San Francisco; and seven grandchildren.

Plans for a memorial service were not immediately available.

Mrs. Dukakis was often a tireless worker and advocate, whether behind the scenes or in a more public fashion, lending her support to a wide range of causes, including women’s rights, the arts, and the plight of global refugees.

Among the many institutions on whose boards she served were the Program on Public Space Partnerships, a nonprofit focused on the design, management, and funding of public spaces; Mapendo International (now RefugePoint), a humanitarian organization serving the resettlement needs of refugees from East Africa; the New England Center for Children, which provides services for children with autism and their families; and the Task Force on Cambodian Children.

Mrs. Dukakis was a fearless, and persistent, advocate for refugees and orphans from war-ravaged countries, including Somalia in the 2000s. She was known to have personally interceded with local authorities on behalf of individuals with whom she kept in touch after they were relocated to America.

At the same time, she expressed frustration at the slow pace of government bureaucracy when peoples’ lives were at risk.

“The United States has been a leader on refugees,” she told the Globe in 2009, “but in the past five years we have left 100,000 refugee slots unfilled. It doesn’t make any sense. It’s absolutely insane.”

Mrs. Dukakis channeled her energies into other areas as well, teaching a course at Loyola Marymount University on 20th-century genocide.

Her work continued through several local and global institutions, among them the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University, where her husband taught for many years after leaving office.

“Kitty had courage,” state Attorney General Andrea Campbell posted on X. “She used her personal pain as a powerful force to help others. Her legacy will live on in the policies she helped shape and the people she inspired to speak their own truths.”

While earning a degree in social work from Boston University in 1995, she was diagnosed with seasonal affective disorder. The affliction became one factor in the Dukakises’ decision to spend subsequent winters in sunnier climes, notably Florida and Southern California.

When depression hit her, she said in a 2000 Globe interview, “It’s not gradual. I wake up in the morning and something isn’t right.” Within a month of its onset, “a real sadness envelops me,” she said, providing insight — and, in some cases, comfort — to those struggling to understand how debilitating substance abuse and depression can be.

In 2006, Mrs. Dukakis published a second book, co-written with Larry Tye, titled “Shock: The Healing Power of Electroconvulsive Therapy,” in which she revealed that, beginning in 2001, she had undergone eight instances of electroconvulsive therapies to treat her depression. They had allowed her to stop taking antidepressants, Mrs. Dukakis noted.

In 2007, Jamaica Plain’s Lemuel Shattuck Hospital opened the Kitty Dukakis Treatment Center for Women, an addiction facility serving the underprivileged.

Mrs. Dukakis was featured in a “60 Minutes” story in 2018 on electroconvulsive treatment. The report included an interview with her and her husband and video of her undergoing an ECT session, one of more than 100 shock treatments she said she had received.

Correspondent Anderson Cooper asked Mrs. Dukakis if she had tried a variety of treatments and therapies to treat her depression before turning to ECT.

“Every kind you can imagine, yes,” she replied, noting that none had been successful over a 17-year period.

For her, ECT had been a life-saver, she told Cooper. “I was just like a new person,” she said, adding that she hoped speaking and writing about her treatment would help others in her condition.

To survive her struggles, Mrs. Dukakis didn’t just seek medical intervention. She often noted through the years that she was sustained by the strength of a marriage so many admired.

“She and our dad, Michael Dukakis, shared an enviable partnership for over 60 years and loved each other deeply,” their children said in their statement.

In her memoir “Now You Know,” Mrs. Dukakis wrote: “I still believe the best thing that ever happened to me was meeting Michael Dukakis.”

Bryan Marquard of the Globe staff contributed to this report. Joseph P. Kahn can be reached at [email protected].