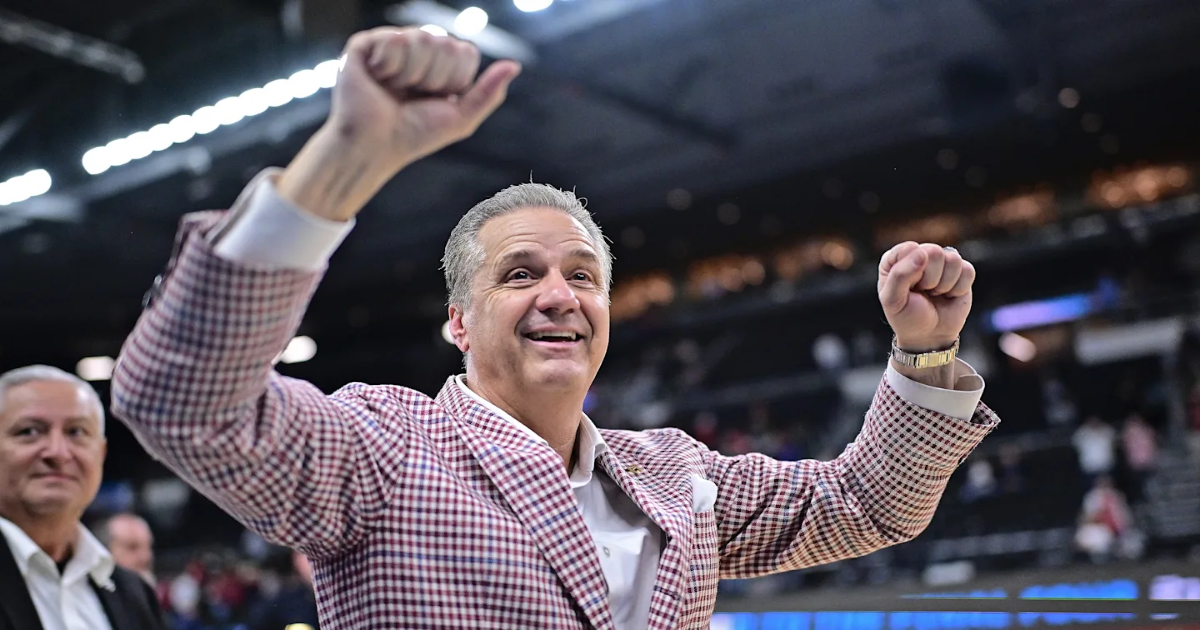

Calipari celebrates after beating Pitino and the Red Storm in the second round of the NCAA tournament. / Ben Solomon/NCAA Photos via Getty Images

The final horn hadn’t even sounded when Rick Pitino started making his way off the court. He congratulated his archnemesis, John Calipari, and the Arkansas Razorbacks staff, then quickly hit the exit into an alcove after what was assuredly one of the most bitter defeats of his brilliant career. The rest of the St. John’s Red Storm trailed well behind their coach after going through the handshake line.

The scene outside the St. John’s locker room was funereal and confusing. Pitino’s top assistant coach, Steve Masiello, conversed quietly with program staffer Kenny Klein. Then Masiello pressed two fingers against the bridge of his nose, as if feeling the onset of a migraine, and leaned against a wall.

CBS reporter Evan Washburn stood nearby against a network backdrop, microphone in hand, as if waiting for an interview with Pitino, but there was no sign of him. Klein took two St. John’s players, Kadary Richmond and Zuby Ejiofor, and escorted them to a holding area for the postgame news conference.

Inside the locker room, the pall was palpable. Reporters clustered around RJ Luis Jr., the Big East Player of the Year, who quietly said he didn’t lead well enough. Luis went 3-for-17 from the field and Pitino benched him for the final five minutes—echoing self-defeating fits of pique the coach had with his star players in 1995 and 2009 Elite Eight losses. (Kentucky Wildcats guard Rodrick Rhodes took the brunt of the blame in the first of those; Louisville Cardinals guard Terrence Williams in the second.)

More. SI March Madness. Men’s and Women’s NCAA Tournament News, Features and Analysis. dark

Pitino stayed out of sight until taking the podium for the postgame news conference, having changed out of his suit and into sweats. He gave Arkansas credit, deflected questions about benching Luis. (“You’re asking leading questions. Don’t ask me any questions. You already know why he didn’t play. … I’m not going to knock one of my players.”)

A man who always has taken losses extremely hard was steeped in the pain of defeat, and also regret. At age 72, he’d performed another in a long series of incredible coaching jobs with this team, winning 31 games, the Big East title and the league tournament. To go out like this, as a No. 2 seed at the hands of a No. 10 coached by a man Pitino despises—this was a gut punch.

“You hate to see us play like that,” Pitino said of the St. John’s train wreck, which included 28% shooting from the field and 9.1% from three-point range. “I don’t mind going out with a loss, I just hate to see us play that way offensively. … It’s just a bitter pill to swallow with that type of performance.”

For Calipari, the taste of this victory was the sweetest he’s had in a decade. Not since taking an undefeated juggernaut to the 2015 Final Four while the coach at Kentucky has the 66-year-old done something this noteworthy. His act grew tired in Lexington, Ky., and he fled for a reboot at Arkansas that got off to a disastrously slow start—at one point the Hogs were 0–5 in the Southeastern Conference. Now they are rolling into the Sweet 16 and rekindling belief in Calipari’s coaching acumen.

“This is as rewarding a year as I have had based on how far we have come,” Calipari said.

Pitino shakes hands with Calipari at the end of their second-round NCAA tournament game. / Gregory Fisher-Imagn Images

Cal did it again to Rick. Their Vivaldi opera of a rivalry has played out publicly for more than three decades, with each man experiencing euphoric highs and devastating defeats against the other. But in recent times the rivalry has swung heavily in Cal’s favor. It has to gnaw away deep inside for Pitino—one of the biggest winners in college basketball history—to lose to Calipari so many times.

For the ninth time in the last 11 meetings between the two coaching legends over a span of 15 years, Cal walked away the winner—this time 75–66 in a men’s NCAA tournament second-round game. Once again, he got his team to play somewhere near its peak, while Pitino’s team stressed out and melted down.

This looked like the 2014 Sweet 16 meeting, when Cal was coaching Kentucky and Pitino was coaching Louisville. The Cardinals were a No. 4 seed on a roll, having won 14 of their last 15 games. Kentucky was a No. 8 seed on the rebound from a disappointing season, talented and still dangerous. Locked into a tougher fight than expected, Pitino’s Cardinals fell apart in the final five minutes and lost to a Kentucky team that would make an improbable run to the national championship game.

It looked like a few of the regular-season meetings between Cal and Pitino when they were at those two rival schools from the Bluegrass State. Pitino’s teams would shoot poorly and get into foul trouble; Cal’s teams would get a season-best performance from someone who hadn’t done much to that point (Dominique Hawkins, anyone?).

The pattern suggests that Cal remains deep in Pitino’s head.

Launching a veritable psyop campaign on Pitino had been one of the objectives all along, ever since Calipari took the Kentucky job in 2009. As one of Cal’s confidants said when he arrived in Lexington, “We want to be the last thing [Pitino] thinks about when he goes to bed at night and the first thing he thinks about when he wakes up in the morning.”

Calipari made it his mission to beat Pitino in recruiting, beat him on the court and beat him in the court of public opinion. A guy whose career prior to that was spent as an antiestablishment disruptor wearing an underdog cape at Massachusetts and Memphis was now at a blueblood, and Cal couldn’t wait to flex that muscle. He’s always relished a fight, and he had an old enemy to go after.

It wasn’t always that way, though. The two men go back nearly 50 years, to the outdoor courts at Howard Garfinkel’s famed Five-Star Basketball Camp. Pitino was a young camp counselor, learning the coaching trade; Calipari first attended Five-Star as a player. Those camps were the birthplace of an endless number of coaching careers, Pitino’s and Calipari’s included.

Pitino’s career went quickly into overdrive, getting the Boston University job at age 25. He had the Terriers in the NCAA tournament in his fourth season—the first of a record six schools he has taken to the Big Dance. Pitino then jumped to Providence and took the Friars to the Final Four in his second year, and parlayed that into the New York Knicks job.

During that time with the Knicks, the UMass graduate became part of a committee to help his alma mater hire its next coach. Pitino said many times that he pushed for Calipari to get the job, and that became part of their running narrative.

Thus the early storylines were all chummy: one demonstrative Italian Catholic coach following another up the ranks, learning the game, saying nice things about each other. After Calipari became the head coach at Massachusetts in 1988, he was often called “Little Ricky.”

But did Cal’s hiring really play out the way Pitino has repeatedly said, including this week in Providence? A 2011 Sports Illustrated story cast doubt on it. The story quotes a member of the UMass search committee saying that Pitino, in fact, did not vote for Calipari to get the job over Larry Shyatt, and debunks a Pitino claim that he wrote a $5,000 check to help cover Cal’s salary.

In the same story, SI writer S.L. Price reported that Calipari “yells in a voice thick with sarcasm, ‘And thank him for all the help he’s given me over my career!’”

Maybe the revisionist history was enough to break the relationship. But in attempting to pinpoint the fundamental fracture, it’s useful to examine the context of a whistle blast in Philadelphia 33 years ago.

There were 5 minutes and 47 seconds left in an East Region semifinal between Kentucky and UMass. Pitino’s Wildcats had led Calipari’s Minutemen by 21 at one point, but the lead had dwindled to two. A significant upset was possible. Tension was in the air.

Kentucky guard Sean Woods grabbed an offensive rebound. Calipari gestured that Woods went over one of his players’ back, wanting a foul call. From across the court, official Lenny Wirtz indeed blew the whistle—on Calipari for a technical foul.

The game swung permanently in Kentucky’s favor. The Cats made the technical free throws, scored on the ensuing possession, then forced a turnover and scored again. They moved on to play the Duke Blue Devils in the greatest game in NCAA tournament history, while UMass went home.

Calipari was incredulous about the T. UMass fans were outraged. Was this a coaching box violation? Or was Wirtz simply fed up with Calipari’s nonstop gesticulating and protesting? Did Pitino put the notion in Wirtz’s ear during the second half that Cal was out of line?

The questions were never answered—then, as now, officials were not made available to discuss their calls.

Calipari said afterward that if it was a call for being outside the box, he would have to live with it. Pitino said the officials told the coaches before the game that excessive histrionics would have consequences.

“Both benches were told,” Pitino said at the time. “And I was told more vehemently than I’ve ever been told.”

Or did the break come four years after that, in New Jersey? Only one of these two insatiable competitors could win a national title that year, and they had the two best teams.

That time, the two met in the national semifinals. UMass was 35–1; Kentucky was 33–2. The Minutemen had upset the Wildcats early in the season, then both teams had gone their separate ways and piled up wins. When they collided in The Meadowlands, the national title was on the line, even if it wouldn’t officially be won until two nights later.

Kentucky won, 81–74, in a game that carried significant pressure for Pitino. He had been, to that point, the greatest active coach not to have won a national title. He nearly went back-to-back the following season, then made an ill-fated move back to the pros with the Boston Celtics.

While Pitino was failing there, Calipari was doing the same with the New Jersey Nets. Their rebound jobs would bring them together for the first time as annual rivals—Pitino with Louisville and Calipari with the Memphis Tigers, both in Conference USA.

The enmity deepened during those years. Before the two teams met in a 2003 game, a Conference USA teleconference carried the whiff of a setup. In a question that felt very much like a plant, a reporter asked Calipari how important the officiating would be in a 2003 game against the physical Cardinals. Cal went on a filibuster about the need for a strong crew that would call fouls. Pitino was not pleased.

“People start talking about officials,” Pitino said. “You know they’ve got psychological problems.”

Memphis won the game in Louisville’s Freedom Hall. The Cardinals were called for 34 fouls.

By 2005, Louisville left C-USA for the Big East. It refused to schedule Memphis as a nonconference opponent, which Calipari decried. But when Cal went to Kentucky, he once again got an annual shot at Pitino. The next few seasons were peak enmity between the two.

Leave it to Oscar Combs, former publisher of a popular Kentucky fan magazine and a product of the Appalachian Mountains in Eastern Kentucky, to offer a homespun description in a 2013 documentary on the rivalry: “Let’s just say that if one was drowning and the other one was standing nearby and no one was around to witness it, you’d have one dead person.”

Whether bracketing serendipity or selection committee machinations were behind it, Pitino and Calipari came to Providence on a collision course. Both won their first-round games—Pitino by blowing out the Omaha Mavericks, Cal in a minor upset over the Kansas Jayhawks. Then they spent the day between games offering up variations on the same themes they have discussed over and over.

“He wears Gucci shoes,” Calipari said. “I wear itchy shoes.”

He trotted out that line Friday. And also in 1992. Both men have reinvented themselves several times, through scandal and loss and a great deal of glory, but they were still playing the old hits.

“I don’t really know a lot about him except he’s a terrific basketball coach,” Pitino said, a statement that defies belief. The two have spent way too much time trying to beat each other for that to be true.

After fighting uphill against Calipari for most of the Louisville-Kentucky rivalry days, this 2025 meeting looked like advantage Pitino. His team was a defensive juggernaut with a heavy fan backing, and expended less effort winning its first-round game than the Hogs.

Razorbacks guard D.J. Wagner drives against Red Storm forward Ejiofor. / Brian Fluharty-Imagn Images

Then the game began, and it didn’t take long for the familiar vibes to emerge. Arkansas’s length and guard quickness were problems. St. John’s shooting, never great, veered into disaster territory. Fouls piled up.

Still, the Red Storm had been a second-half team all year. And Arkansas was no offensive masterpiece of a team itself, prone to poor shooting and long lapses in scoring. Sure enough, St. John’s battled back, over and over.

The key moment was with Arkansas leading 66–64 in the final minutes. Big man Ejiofor, who played a lionhearted game for St. John’s, had a tying layup that he shot clean over the rim. Arkansas scored on the next possession for a four-point lead, and the moment had passed Pitino’s team by.

Calipari’s team made all the winning plays, with an ensemble of players who the coach said had to work themselves out of “a dark place” during the season. This was testament to a season of persistent and patient coaching by Cal—not giving up on his players, coaxing the unit through various injuries, imbuing everyone with a confidence that they would, eventually, become great.

“We can’t trade anybody,” he said he told his staff during the ugliest parts of the season. “This is who we got. Let’s go to work making them better.”

Saturday in Providence, they were good enough to take down No. 2 seed St. John’s and advance to a very Sweet 16. The latest chapter in the never-ending story of Cal vs. Rick went to Cal, as so many others have. More than he’d ever admit, Pitino’s headspace is occupied by his onetime protege and longtime nemesis.

Published 12 Minutes Ago|Modified 10:23 PM EDT