For the last quarter century, one of the world’s most capable drug developers toiled to make a new, non-addictive kind of painkiller. The journey was fittingly excruciating.

Pain, as Vertex Pharmaceuticals found out, is wildly complex. It starts simple enough, with a sliced hand or burned finger or broken bone. But it convolutes fast. Special nerve cells, activated by potentially dozens of chemicals and proteins, sense the pain and launch a signal up the spine like a firework, lighting up a patchwork of brain regions that interprets this message and decides how the body will feel.

Much about how this process unfolds in any given person remains hazy. Scientists suspect genetics, past experiences and the environment each play some role, perhaps explaining why two people who suffer the same injuries can have such dissimilar pain. This intricate web tripped up many of the world’s most adept pharmaceutical firms, a key reason why no truly innovative medicines have come forward in more than two decades.

Vertex was one of the few to trudge ahead. Its pain labs in San Diego discovered, fine-tuned and tested promising compound after promising compound. Invariably, though, studies would show them not safe or potent enough to meet Vertex’s exacting standards. Not until about 20 years into its hunt did the company find a molecule worth championing.

On Thursday, the Food and Drug Administration approved that molecule, now called Journavx, as a treatment for the sharp, short-lived “acute” pain usually felt after an accident or a surgery. Expectations around Journavx are high. With the U.S. still mired in an overdose crisis that’s killed hundreds of thousands of people, Vertex is positioning its medicine as a valuable alternative to opioid-based therapies.

Doctors say they’re eager to have another tool at their disposal. Wall Street views Journavx as a billion-dollar product.

Journavx has a real chance to “bend the curve on the opioid epidemic,” said Stuart Arbuckle, who, as Vertex’s chief operating officer, is overseeing the drug’s launch. “This is the first real alternative. The other is to leave these people in pain, and that’s not an acceptable choice.”

Yet the true impact of Journavx will hinge on whether Vertex can contend with a healthcare system that favors the cheapest possible option — a system which, at the hands of drugmakers, insurance companies and pharmacy middlemen, was gamed for opioid use. Doctors across the country, from Oregon to West Virginia to Massachusetts, envision the biggest barrier to prescribing Journavx being insurers, as they tend to resist covering new, higher-cost pain drugs. Vertex set the medicine’s price at $31 a day, many times more expensive than generic opioids like hydrocodone.

Pain is unlike any other drug market, presenting both an opportunity and a challenge for Vertex. The least expensive therapies have ruined countless lives, and wreckage from the opioid epidemic has, for some time, prompted a shift to a layered treatment approach that tries to use these powerful drugs only as a last resort. Vertex’s mission is to convince doctors and insurers that Journavx belongs somewhere in the mix.

Arbuckle claims, as industry executives often do, that his team has had fruitful conversations with these stakeholders, that they appreciate Journavx may fill a major gap in pain management. They’ll need to for most patients to have a shot at accessing the drug.

“In some ways, talk is cheap,” Arbuckle said. “It really will depend on what we see from people in terms of action in the days and weeks following approval.”

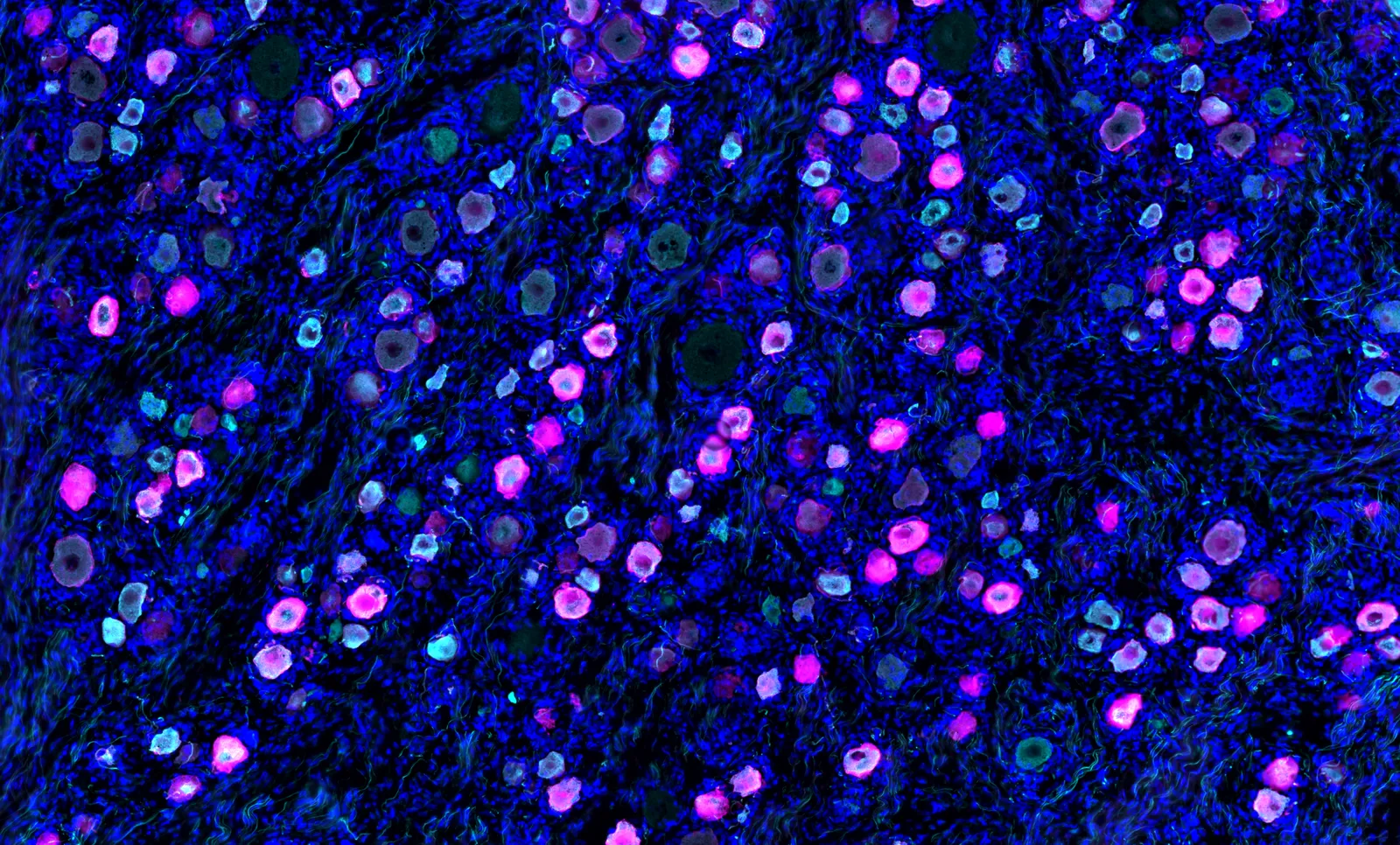

Journavx targets in peripheral nerve cells an ion channel called Nav1.8, colored magenta in this immunofluorescence image.

Permission granted by Nwasinachi Adriana Ezeji/Center for Advanced Pain Studies, University of Texas at Dallas

Supporting Vertex’s case are a pair of large clinical trials that assessed Journavx in people who underwent either a “tummy tuck” or a bunion removal, two notoriously painful surgeries. Both experiments showed the drug was significantly better than a placebo at easing pain. It also worked decently fast. Participants reported some relief within a few hours.

Unlike all other approved pain drugs, Vertex’s blocks tube-shaped proteins found almost exclusively in nerve cells located outside the brain and spinal cord. These “NaV1.8” proteins act like cell towers, transmitting pain waves to the central nervous system. In addition to being effective, studies have found Journavx to be remarkably safe. It doesn’t appear to have the addictive qualities of opioids, which bribe the brain’s pleasure centers, and compared to a placebo it actually was associated with lower rates of common ailments like nausea, constipation and headache.

Vertex took these results and asked the FDA for a broad approval in moderate-to-severe acute pain. With that now in hand, Vertex can enter the segment of the pain market where opioids are more readily prescribed. The company has also been sponsoring research to expand into different types of chronic pain.

There, Journavx has delivered mixed results. Vertex lost $15 billion in market value in December when data from a lower back pain trial disappointed investors. A year earlier, however, a study focused on the chronic nerve pain caused by diabetes showed Journavx to be about as effective as the main ingredient in Lyrica. Analysts described that performance as “solid” and “strong.”

Journavx has other limitations. The two acute pain studies explored whether it is superior to a combination of Tylenol and a commonly prescribed opioid. On that measure the drug fell short, a “glaring” outcome for Richard Vaglienti, medical director of the Center for Integrative Pain Management at West Virginia University, which treats roughly 1,600 patients a month.

Vertex rejects that this finding will be a hangup. “Go and ask physicians and patients,” Arbuckle said, “they’ll tell you that’s not what they’re looking for.”

Vertex did just that last year, commissioning a survey of around 550 healthcare providers and 1,000 adults recently treated for acute pain. Their bigger concerns, according to the company, were the addictive potential of opioids and the exigencies of having few non-opioid options.

Taken together, Vertex’s data have left many experts with a positive view of Journavx, yet no firm agreement on precisely which scenarios it is best suited for. Vaglienti thinks it’s “possible” the drug could have a “decent role to play” managing non-severe chronic pain, and might be particularly useful for patients who can’t tolerate more potent drugs.

Kimberly Mauer, vice chair of the pain center at Oregon Health & Science University, sees it as more widely applicable. “This sounds like an exciting option, because it’s going to be opioid-like, and maybe not have the side effects or the risk,” she said. “And if it doesn’t work as well as opiates, I’m OK with that. Because I can maybe pair it with something else.”

While drug research and opioid mitigation strategies often focus on chronic pain, having a pill like Vertex’s in the acute setting is “extraordinarily important,” said Theodore Price, director of the Center for Advanced Pain Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas. That’s because many people are susceptible to opioid addiction but don’t realize it until they’ve been prescribed the drugs following a trauma or operation.

Tens of millions of surgeries happen annually in the U.S. And while estimates vary depending on the period studied, recent research indicates a large portion of surgery patients are still prescribed an opioid.

“There’s nothing you could say that could convince me this doesn’t have an impact on what happens to them later on in their life, at least some portion of them,” Price said.

Accidental overdoses involving an opioid remain high. Nearly 82,000 people in the U.S. died that way in 2022. Almost 15,000 of those deaths involved a prescription opioid. Price himself lost one of his best friends to an overdose about 15 years ago, after the friend was first exposed to opioids for pain management.

“It’s a tragedy,” he said. “If we could have a drug that would help us to avoid this, it would be an absolutely massive benefit to humankind.”

Addiction treatment can help people with opioid use disorder, but researchers have found that insurance rules can limit access to medicines like buprenorphine.

Permission granted by OHSU/Kristyna Wentz-Graff

Jose Zeballos understands this need well. As an anesthesiologist and leader of the acute postoperative pain management service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Zeballos cares for hundreds of patients every year. A few advances in treatment have emerged during his tenure, like new, longer-lasting local anesthetics, but overall “nothing else has come out that really has helped.”

Vertex’s medicine could therefore be an “amazing” addition, he said, as it may offer some relief not only after surgery, but in everyday pain management as well. Journavx might dull persistent back aches or take the edge off a sports injury. And, since opioids can confuse and disorient, it could be an especially valuable alternative for elderly patients.

Despite the many use cases, Zeballos predicts doctors to reach for Journavx only if it’s “easily accessible,” and that depends on insurance companies stomaching the drug’s price tag. “It probably all comes down to financials more than anything else.”

Arbuckle says price and access are by far the biggest issues brought up when Vertex’s commercial team discusses Journavx. Millions of prescriptions for acute pain are written every year in the U.S., so, from the payer perspective, “if you’re seen millions of anything, you’re worried about the budget impact.”

Generic opioids like hydrocodone cost less than $2 a day. Advil and Tylenol are cheaper still, making Journavx’s price of $31 a day high enough to draw close examination from insurers.

Arbuckle argues that’s the wrong comparison, since it doesn’t account for the devastation opioids bring to both the healthcare system and society at large. A report from the Congressional Joint Economic Committee tried to calculate this cost and, looking just at 2020, assessed the total at nearly $1.5 trillion, one-third higher than three years prior.

“This is not an academic, side-by-side, two things have equivalent efficacy and one’s cheap and the other one isn’t [exercise],” Arbuckle said. “Every time a physician and patient chooses [our drug] when they would previously have chosen an opioid, that is one less opportunity that person is exposed to the potential liabilities of opioids, gets opioid use disorder and becomes a horrible statistic.”

Vertex is beholden to investors as well as patients. The price set by the company may have societal value baked in, but it’s also meant to drive revenue. One analyst expects Vertex’s pain portfolio, which includes Journavx and a series of follow-on drugs already in development, could eventually generate north of $10 billion a year.

Analysts at the investment bank Cantor Fitzgerald recently spoke to a senior director of product development at one of the nation’s largest insurers, UnitedHealth Group. The director predicted Journavx will get broad coverage, as payers are under serious pressure to cover non-opioid medications.

He also doesn’t anticipate the drug will be subject to “step therapy,” a controversial insurer practice that requires patients to “fail” on cheaper drugs before trying newer, pricier medicines.

Optum, a pharmacy benefit manager owned by UnitedHealth Group, declined to answer BioPharma Dive questions on its coverage plans for Journavx. Insurers Humana, Cigna and CVS Health did not respond to requests for comment. Vertex has talked to payers as well as parties that “paid billions of dollars for their role in the opioid epidemic,” according to Arbuckle, and the conversations have been “really positive.”

“Virtually everybody we speak to totally gets it,” he said. “Does that mean we’re going to have tough negotiations on price? Of course. Do we think we’ll have to negotiate access? Of course. Do we have to go through formulary procedures? Of course. But it’s not like we’re getting a stiff arm from people.”

If Vertex does get payer buy-in, Journavx could be an exception to a longstanding, unwritten rule in pain management: fresh therapies take a while to reach patients. One of the company’s immediate goals is to cut down this timeline and to make sure, if patients are prescribed Journavx, they can pick it up over the counter at their local pharmacy.

At OHSU’s pain clinic, Mauer said her team rarely uses new medications within months of them coming to market, because insurers haven’t yet decided coverage plans and the out-of-pocket costs are too high for most patients. Nine times out of 10 the wait is “pretty long.”

“The problem with any new drug is the reluctance of insurance companies to pay for it because of the heavy upfront cost,” Vaglienti said. “So even though there are risks with opioids, from the insurance company side, 30 Percocet really only costs a few dollars.”

Vertex Pharmaceuticals researchers work in the company’s San Diego laboratories.

Courtesy of Vertex Pharmaceuticals

Journavx, then, may serve as a proving point for Vertex. The Boston-based biotechnology company has grown to an almost $115 billion valuation by selling big-ticket medicines for uncommon diseases with few to no other remedies. Pain has a trove of generic treatments and, just in the acute setting, Vertex approximates 80 million adults in the U.S. are prescribed a medicine each year.

Pricing barriers like the ones facing Journavx can be overcome, though success often takes time. Between 2018 and 2020, a novel class of injectable migraine drugs came onto a market flush with generics. While one is now approaching blockbuster status — $1 billion or more in annual sales — the others remain only modestly successful. A similar dynamic awaits a new schizophrenia treatment from Bristol Myers Squibb, which, while pegged for success, faces numerous, lower-cost competitors.

Journavx’s launch comes at what might be considered an opportune time. The reckoning over the opioids still lingers in the public eye. Just last week, members of the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma agreed to pay as much as $7.4 billion in a revised legal settlement over the OxyContin maker’s role in the epidemic.

Federal and state lawmakers are also taking action. Two Congressional bills — one enacted this month, the other introduced in the Senate last year — aim to amend Medicare so older Americans can more easily access and afford a list of certain non-opioid pain medications. Journavx is eligible to join this list, though it likely won’t be added until at least 2026.

Policies like these could help “level the playing field” in the pain market, Arbuckle said, and their arrival represents a “turn in the tide.”

The executive is adamant that Vertex can make the most of this momentum. It’s been preparing for Thursday’s approval for “a number of years now,” he said, and has amassed 150 staff to sell Journavx.

Still, there are doubts the launch will go as smoothly as Vertex — or its investors — might hope.

RBC Capital Markets analyst Brian Abrahams is braced for “limited initial adoption” and thinks the $90 million figure that other analysts have forecast for 2025 sales is “optimistic.” Paul Matteis of Stifel shares those reservations. In acute care, he said, “it’s almost impossible to find a good drug launch” for anything non-lifesaving, in large part because the field “moves really slow” to adopt new treatments.

Both analysts note that, for Journavx to hit that $90 million mark, hundreds of thousands of patients would need to take the drug. “No one has a clue how to model it,” Matteis said.

The medical and research communities may be holding their breath, too. Price, of the University of Texas, fears that if Vertex doesn’t make a strong enough case, it could dampen enthusiasm around Journavx or even broader pain research.

“Any medication that is effective for treating pain of any type, that doesn’t have all the negative things associated with opioid therapy, would be extremely valuable,” said Vaglienti. “And I know the company is probably banking on this being one of those medications. That will remain to be seen.”